Sunday, February 28, 2010

Thursday, February 25, 2010

To My Drawing Class- In Memory of Kristoffer Hjelle

In the time our class has been together we’ve become a community and a group mind comprised of many different ways of seeing. Losing Kris is a tremendous blow to us. His way of seeing and expressing itself broke boundaries in every direction.

In the community organism our class has become we need to stop and digest how the way Kris thought has influenced the way we think. As I write this I’m listening to a sound piece he made for me with binaural beats and nature sounds. He addressed my interest in meditation and the brain and combined it with his own sensitivity to nature. His ecological consciousness, including a compassion for all beings, turned up throughout his work. He pushed experimentation with media and the structure of drawings and ways to think about art that we can in some way metabolize, build into our own creative being. He broke down boundaries between different disciplines, combining imagery with sound and interactivity. We can build our own possibilities by the inclusion of his.

We can develop the neural circuits that were affected by his presence in the class, whether it was identifying with his ideas, his sensitivity, his use of media, or his willingness to structure drawings in entirely different ways. There was a boundlessness to his creativity that we can reflect on when we feel restricted.

Thinking about how he influenced us, remembering how our lives were touched, on some level makes him more present through the focus of our attention. Last Thursday night, looking at the hand stitched book he was making, I told him that some of what he’d written represented deep spiritual insight. He was very wise about the pitfalls of the human mind. This showed clearly in some of the papers he wrote for Amy Eisner’s class. He wrote, “We must not always look to etymology, history, or any other established approaches to find understanding, because the truth is that in one word, there is a bible of meaning and although an artist makes his own path, so will the reader. I say ditch the path and create your own.” This was his challenge to us.

When we reclaim the complete life of a person, we can feel all of the ways their way of being affected us and extended our understanding of how people look at the world. We may have shared an opinion and felt affirmed that someone as smart as Kris was thinking along those lines. He and I had conversations that I thought about long afterward and often changed the way I was looking at a subject. His ideas will have reverberations throughout the rest of my thinking. The length of a life has nothing to do with its value.

Recognizing how Kris has affected us enables us to deepen and grow and be grateful to him as the source of greater light.

In the community organism our class has become we need to stop and digest how the way Kris thought has influenced the way we think. As I write this I’m listening to a sound piece he made for me with binaural beats and nature sounds. He addressed my interest in meditation and the brain and combined it with his own sensitivity to nature. His ecological consciousness, including a compassion for all beings, turned up throughout his work. He pushed experimentation with media and the structure of drawings and ways to think about art that we can in some way metabolize, build into our own creative being. He broke down boundaries between different disciplines, combining imagery with sound and interactivity. We can build our own possibilities by the inclusion of his.

We can develop the neural circuits that were affected by his presence in the class, whether it was identifying with his ideas, his sensitivity, his use of media, or his willingness to structure drawings in entirely different ways. There was a boundlessness to his creativity that we can reflect on when we feel restricted.

Thinking about how he influenced us, remembering how our lives were touched, on some level makes him more present through the focus of our attention. Last Thursday night, looking at the hand stitched book he was making, I told him that some of what he’d written represented deep spiritual insight. He was very wise about the pitfalls of the human mind. This showed clearly in some of the papers he wrote for Amy Eisner’s class. He wrote, “We must not always look to etymology, history, or any other established approaches to find understanding, because the truth is that in one word, there is a bible of meaning and although an artist makes his own path, so will the reader. I say ditch the path and create your own.” This was his challenge to us.

When we reclaim the complete life of a person, we can feel all of the ways their way of being affected us and extended our understanding of how people look at the world. We may have shared an opinion and felt affirmed that someone as smart as Kris was thinking along those lines. He and I had conversations that I thought about long afterward and often changed the way I was looking at a subject. His ideas will have reverberations throughout the rest of my thinking. The length of a life has nothing to do with its value.

Recognizing how Kris has affected us enables us to deepen and grow and be grateful to him as the source of greater light.

Friday, February 12, 2010

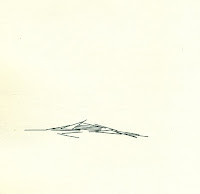

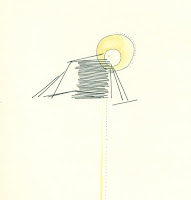

Art Showing Feeling

√ It was after completing a series of very simple drawings in 1976 that I began to think art could be a useful tool to help people recognize their feelings. They were exhibited that spring at the Image Gallery in Stockbridge, MA. I was pleased and somewhat surprised at the reception they received, since my work is usually very detailed and I thought that was part of its appeal. Stacks of lines in varying degrees of balance, the drawings seemed like shorthand for expressing feelings difficult to describe in words. Anyone could immediately recognize how they were “stacked up” at that moment, how balanced they felt at any given time. When I went to work in a short term counseling facility, I quickly saw their potential usefulness. Often the reason it’s so hard to tell a counselor how you feel is because there aren’t really words that fit. Each word puts the feeling into a definition that may not really match. I adapted my series to hang in one of the counseling rooms, nine drawings ranging from total collapse to perfectly balanced. They seemed to make a difference, enabling counselor and client to get to the point more quickly and lay out the situation contributing to that state. Though I left after two years, the pictures stayed in use for the next seven. (The ones I’m posting are from the original series). It occurred to me after posting my last essay that anyone who wanted to reflect on their inner state could draw a stack of sticks and see how they feel, what mood they’re in, how they stack up that day. I thought I’d offer these up by way of encouragement to try your own.

Talking with students about my own drawing process I emphasize that I don’t know what’s going to happen when I start. I lay out big shapes and color fields in a way that feels right until the whole page is divided into a particular state of balance. When I look at it I’m often surprised at what it shows me. I’ll think, “Hmmm, I’m in worse shape than I thought.” Usually that thought makes me snicker at the immediate insight into my whole circumstance.

For the deep psychological strata, nothing is better than looking at great art. To look at a portrait by Rembrandt you can see your own deepest questions looking back. Current art challenges aspects of our immediate culture, and it can be deeply reassuring to see others pointing beyond the surface descriptions. In every case, it’s not just the recognition that we’re more than the boxes we’re put in, but the enlarged perspective we gain that is the best kind of learning. Since learning produces endorphins, the acquisition of more perspective makes us feel better. Great art shows us how much bigger we are than the world makes us think. When an artist hits my current state of mind dead on, I laugh out loud.

Drawing is a way of thinking visually. Whether your doodling during TV or depicting the detail on a dead leaf, you are showing yourself something your brain is trying to see. The doodle may have a musical feel in the repetition of similar shapes and have the same soothing effect. Drawing what you see develops powers of observation as well as showing what in your surroundings you care enough about to want to see better. Observation is the foundation of art and science. Building that skill serves you well in every way imaginable. It shouldn’t be reserved for artists. It develops a hemisphere of the brain long neglected by the dominance of words. Everybody should get a pad and see what they feel.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)